Several years ago, a colleague came for dinner and brought me a seven-year-old cheese in a can. Do you say “thank you” for what seems like a gag gift? Was she suggesting that I might actually enjoy a cheese that’s packed in a tin like cheap tuna? Well, I did. And you will. If you want this uniquely American cheese for your Thanksgiving table, don’t delay. The shipping charge just dropped for most of the country, and the supply will sell out soon.

Thank you, Laura Werlin, for introducing me to the utter delight of an aged Cougar Gold. The truth is, even young Cougar Gold is a treat. And if you want an aged one, you have to mature it yourself because Washington State University—whose students make this Cheddar-style cheese—sells out its production every year. As the creamery manager told me years ago, the way to get an aged Cougar Gold is to “throw it in the fridge and try to forget about it.”

The university’s dairy science department has been making Cougar Gold since the 1940s. The cheese is named after the school mascot and N. S. Golding, the dairy science professor who helped develop it. The cow’s milk comes from the university’s own dairy farm and, since demand has grown, from the neighboring University of Idaho dairy farm, just a few miles away.

University students, who are paid for their labor, produce this cheese, and revenue from the cheese supports the dairy-science program. The student who adds the culture to the vat is considered the cheesemaker for that batch, and his or her name is stamped on the tins along with the make date. The tin I bought recently said that Andrew made it on June 6, 2020. A geology student then, Andrew Constantino has since graduated and now works for the creamery.

Cougar Gold is a Cheddar with some differences, most obviously the unconventional packaging. In the 1940s, the federal government and the American Can Company partnered with the university to explore how to preserve cheese in a can. Plastic packaging was in its infancy then.

Alas, cheeses emit carbon dioxide, which was causing the cans to bulge or blow. Creating a less-gassy Cheddar was Golding’s assignment, and he achieved success with a “cocktail” of cultures. One of these cultures is now proprietary and maintained by the students; it contributes a nutty flavor.

Most moderately priced Cheddars are made in 40- or 640-pound blocks and aged in plastic bags. But Cougar Gold has to fit in its can, and I’ve been puzzling over how they do that. Creamery manager John Haugen told me the curds are pumped into log-shaped molds the same diameter as the can. After pressing to remove more whey, the logs are sliced into disks.

Get the recipe: Cheddar with Cranberry-Pear Chutney

Most of the Cougar Gold in the university’s stock is 12 to 16 months old. If you want to stash it away, unopened, in the fridge, it will only improve, developing crunchy crystals and a crumbly texture. Haugen says he once tasted a 37-year-old Cougar Gold.

“Sometimes customers will bring us an old one and ask to trade,” says Haugen. “Usually they find it in the fridge after a relative dies.”

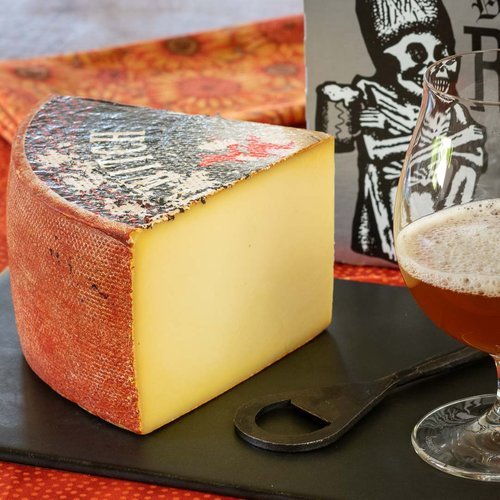

He says the cheese gets notably sharper with age, but I recall the seven-year-old as pretty mellow. The tin I just opened—at 16 months—was even more so, a creamy, faintly nutty and gently tangy Cheddar. I was happy not to find the fruity pineapple scent and sweetness that turn up in so many American Cheddars these days. Haugen says the recipe has hardly changed over the decades. Years ago, they reduced the salt percentage and switched from animal to microbial rennet. But otherwise, you’re tasting the cheese that Golding created.

Because of cooler autumn weather, the creamery will now ship its cheese to most parts of the country via standard ground carriers. My shipping cost was $8, on top of $25 for the cheese. That’s a steal.

Add Cougar Gold to your Thanksgiving relish tray, or bring it out for holiday parties. It’s a great conversation starter. Pour a pale ale if you’re a beer fan; a Zinfandel seems like the right wine choice for this all-American classic.