It’s such a bummer when a great creamery shuts its doors, and this fall brought a double whammy. First, we lost a fine American cheesemaker to vascular disease in mid-September, and his family has decided not to soldier on. Now we learn that one of the most admired British cheesemakers—producer of a superb award-winning sheep cheese—is tossing in the towel. What makes this news even more troubling is that both cheesemakers were farmstead producers working with raw milk from grass-fed herds—a small niche that seems to grow smaller every year.

“As much as people say, ‘Don’t make rash decisions,’ I knew it would be impossible for me to continue cheesemaking,” said Leslie Jacobs, who ran the business side of Jacobs & Brichford with her husband, Matthew Brichford. “How am I going to keep a dairy herd going? I had a number of people say, ‘I’ll buy a cow,’ but we had 67.”

Due to drought in the Midwest, the cost of hay has soared. Jacobs realized she could not afford to feed the herd this winter, if she could get hay at all. Matthew had been in poor health and unable to make much cheese over the past couple of years, so the creamery’s revenue had plummeted.

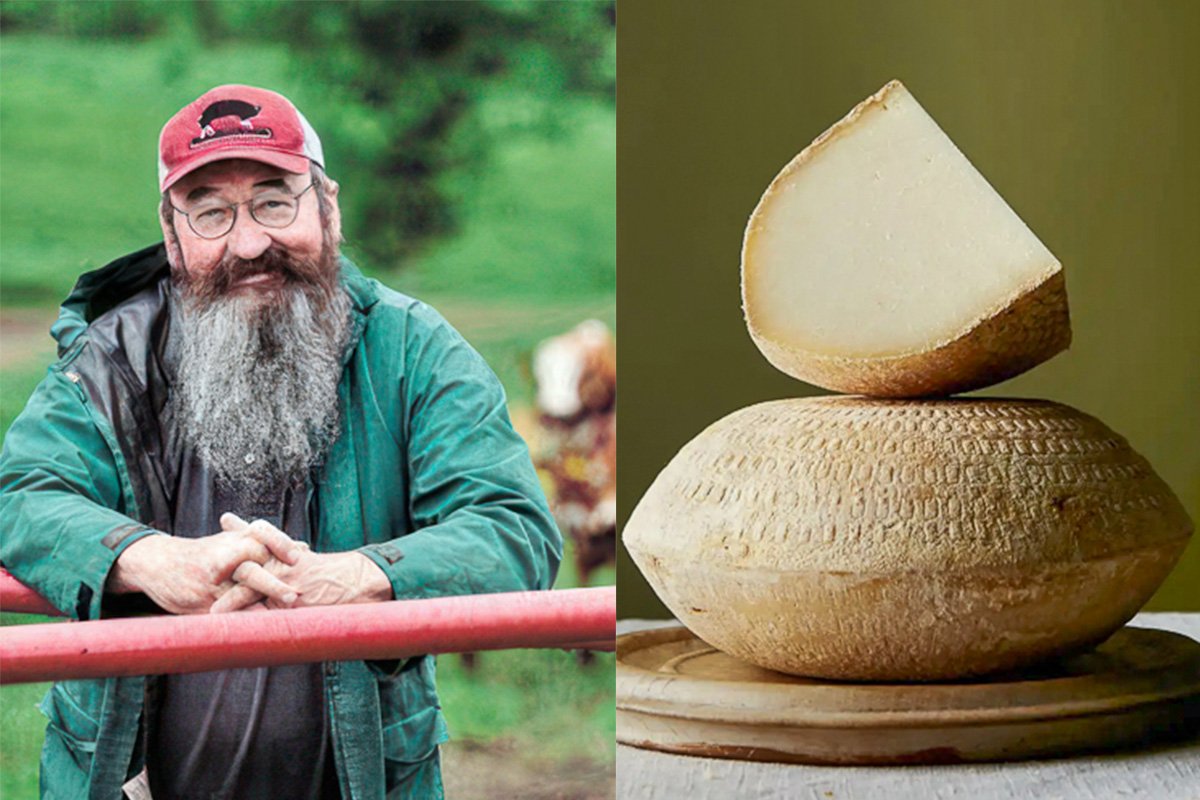

Washed-rind gem: Jacobs & Brichford Ameribella

The Brichford family has operated their Indiana farm since 1819, more than two centuries. Matthew and Leslie introduced cheesemaking there in 2012, with critically acclaimed efforts like Ameribella and the alpine-style Everton. Ironically, just a few weeks after his passing, two of Matthew’s cheeses won gold medals at the prestigious World Cheese Awards.

Like many farmers, Matthew did not have an exit strategy. He and Leslie had three daughters, who all had other plans. “It was hard for him to swallow that the kids weren’t interested in taking this over,” says Jacobs. She recently sold the herd at auction, a traumatic experience.

Indiana cattle ranchers don’t value dairy cows, even top breeds like Jerseys. The proceeds were underwhelming. The Brichford family will continue with beef cattle, but the cheesemaking is history. If you would like to try Jacobs & Brichford cheeses before they disappear, you can purchase them from the creamery’s online store.

I’m also in mourning for Berkswell, an aged British sheep cheese made in Coventry since the late 1980s by the Fletcher family. (No wonder I love it.) Formed in a colander, it has an eye-catching shape and captivating aromas of brown butter and caramel. From the get-go, Berkswell was pricey and worth every cent.

“It’s hugely well respected,” says Ruth Raskin of Britain’s The Fine Cheese Co., which distributed Berkswell in the UK and exported it to the U.S. “To me, it’s the hard sheep’s milk cheese of the UK, absolutely the bedrock. It would be my essential cheese in my cheese shop.”

Moving on: Berkswell sheep

So what happened? According to Raskin, Stephen and George Fletcher—the father-and-son team who managed the flock and made the cheese—are simply burned out.

“I don’t think Stephen has had a weekend off or a holiday in as long as he can remember,” says Raskin. “It’s all consuming. Sheep aren’t as easy to look after as cows, and it’s harder to find people to help you.”

The devilish detail about the sheep cheese business is that dairy sheep produce so little milk. “Your average consumer doesn’t understand that the effort and love is exactly the same (as for cow’s milk cheese) but you have less product at the end,” says Raskin.

At least the Berkswell flock is going to a good home—to a farm in the Cotswolds that makes vodka from sheep’s milk whey. David Jowett, a talented young cheesemaker who trained at Berkswell, will use the milk for a cheese that’s still in development. The whey will become vodka and Stephen will manage the sheep, at least in the near term.

A final shipment of Berkswell should arrive in the U.S. in early February, says Debra Dickerson, a U.S. representative for The Fine Cheese Co. The wheels will be parceled out to independent cheese shops and high-end retailers “who appreciate the significance of this loss,” says Dickerson. Keep your eyes out for it.